Why the United Kingdom should leave the European Union

The EU is not the future. Regional blocks are outmoded concepts, trans-national multi-ethnic states are breaking up across the globe. Peoples around the world want self-government and devolved decision making. Modern political developments are dominated by the abolition of old blocks and the creation of new nation-states that are more homogenous. Change is coming which will lead to the dismantling of the EU.

The EU cannot be reformed to suit British sensibilities. The commitment to ever-closer Union was enshrined in the treaties that govern the EU and it is fanciful to presume that the European Commission, the institution with the sole right to initiate legislation in the EU, and its ally the European Court of Justice (ECJ) will abandon the politically supported quest to further establish a government for governments in Europe. Therefore, change will come from the people acting through nation-states that wil assert their independence.

The British people, just like an increasing number of European citizens in other EU states, are ill-at-ease with their national democracies being subordinate to the unaccountable institutions of the EU. The political and economic costs are just too great.

The European Union is most definitely in relative, if not actual, economic decline. According to a report by the European Commission titled Global Europe 2050, in 2000 the EU accounted for 25% of world economic output. However, by 2050 its share of global GDP will be "as low as 15%". The EU’s own report goes on to say that, "by 2050, Europe’s share of global economic product may be lower than it was before the onset of industrialization, hardly a trend leading toward global economic dominance" 1.

Future prosperity lies elsewhere. The UK’s trade with the rest of the EU has fallen, in goods and services, by over 13% since the year 2000. Over the same time frame it increased by 12% with the rest of the world. No doubt there are emerging markets around the globe that present new and exciting opportunities for British businesses 2.

It is time to re-energise our national democratic institutions and re-engage with the rest of the world. This can only be done by exiting the EU.

There are many faux claims about the supposed benefits of EU membership. The growing unemployment queues across the continent tell a markedly different story. One myth is that membership is required for trade and to access the EU’s internal market. But this ignores the fact that the EU has 45 free trade agreements with other nations around the globe, and this list is growing.

There is every reason to believe that business in the United Kingdom will still retain full access to the EU’s internal market, whilst severing the political control of the Brussels and Luxembourg based institutions.

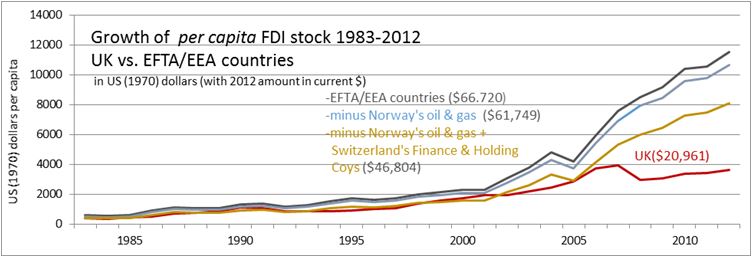

There are also other nations in Europe that are not in the EU yet belong instead to the European Free Trade Association (EFTA) Iceland, Liechtenstein, Norway and Switzerland. These are amongst the most prosperous countries on the continent and benefit the most from Foreign Direct Investment (FDI), the direct business investment by overseas companies which is a good indicator of an economy’s health.

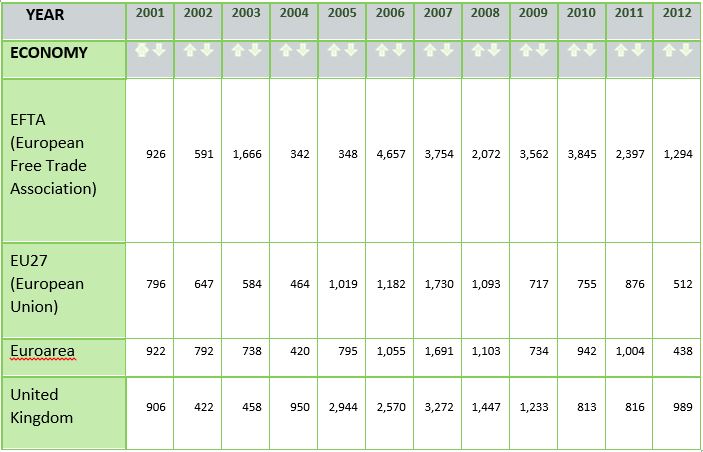

Evidence from United Nations Conference on Trade and Development (UNSTAD) shows both that the EU is suffering from a shortage of FDI and that the EFTA states benefit from being outside of the EU. In terms of FDI counted in US dollars per capita, it is clear that membership of the European Free Trade Association benefits its members far more than membership of the EU.

Foreign Direct Investment flows per capita per year (US $)

FDI in Iceland, Switzerland, Norway in comparison with the UK (1983 – 2012) 3

Sources : UNCTADstat Foreign direct investment stocks and flows, annual, 1970-2012

Central Bank of Iceland, 1989-2012

The cost of the EU is ruinously high. The UK’s gross payments in the 2014 – 15 financial year will reach more than £18.7 billion with a net contribution, less the rebate and EU spending in Britain, totaling nearly £9.37 billion per year 4. Britain is quite clearly better off out.

Repeatedly the British taxpayer is hit with demands for more payments to the EU. This is not the only cost. Both Oxfam and the Paris-based Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development estimate that the Common Agricultural Policy costs the average family around €1,000 per year.

The OECD have estimated that the higher taxes and food prices caused through agricultural protectionism costs the family of four $1,000 per year. With food prices being as much as 30% higher than food which is traded internationally 5.

To whose benefit are these resources being spent? It is believed that the CAP’s agricultural support payments are intended for small farmers, however Oxfam make the case that 80% of the support goes to the wealthiest land owners and the largest agricultural businesses. The OECD estimate that ‘Of every $1 in price support, only $0.25 ends up in the farmer’s pocket as extra income. The rest is absorbed by higher land prices, fertiliser and feed costs and other factors 6.’

That, however, is just one of a number of ways that once independent nation-states are subordinated to the institutions of the EU. Whole tranches of policy making no longer rest within the remit of national democratic institutions. There are numerous other examples of wrong-headed EU policies the list is growing. Some have claimed that excessive EU regulation is a major drag on prosperity and economic growth.

Indeed, the complete body of EU law is known as the acquis communitaire and runs to more than 170,000 pages of active legislation which is in force, with over 100,000 EU rules, international agreements and legal acts binding on or affecting citizens across the EU.

This body of law is added to at the rate of around 3,000 new pieces of legislation each year. How many of Britain’s new laws originate or are influenced by the EU?

A study by the House of Commons Library found that more than 50% of the UK’s new laws come from Brussels or are influenced by the requirements to adopt EU rules. What is more, the British Parliament has to impose criminal sanctions if an EU law has been contravened. This is legislation that the democratic institutions of the UK have little influence over.

It is widely thought that these rules have no basis in commonsense. Yet it is not just British people that hold this view.

This mass of EU law and the burden of overregulation is often cited by those who want outside of the EU. This is seen as being an even greater cost than the direct cost placed on the taxpayer. It is argued, and almost universally believed that, excessive laws hold back economic growth by as much as 5.5% of GDP. The source for this estimation is non-other than a then serving Vice-President of the European Commission Günter Verhuegen 7.

On 10th October 2006 Günter Verhuegen, who was also the then European Commissioner for Enterprise and Industry stated that,

‘Many people still have this concept of Europe that the more rules you produce the more Europe you have. The idea is that the role of the commission is to keep the machinery running and the machinery is producing laws. And that's exactly what I want to change.’

Verhuegen’s bid for reform was, however, blocked according to the Commissioner by the EU’s administrative culture 8. Even the Vice-President could not stop the legislative avalanche.

The basic process of how Brussels works shows that much influence rests with the political, but unelected, bureaucrats. The Council of Ministers, the representative arm of, and from, the member states including Britain, receives proposals from the appointed Commission, asking them to take powers away from their governments thus depriving their own citizens of power. From then on, the Commission having been given the power, it keeps it, to exercise as it sees fit.

Does the Council maintain an oversight over how those powers are exercised?

No.

Has the Council any power to call the Commission to account over the way it uses its powers?

No.

Can the Council remove or modify those powers, if it is unsatisfied with the way the Commission is performing?

No.

Does the Council even have the power to ask the Commission for information on its performance?

No.

That is not a system where the democratically elected governments of the nation states can hold the Commission to account. The other ‘democratic’ arm of the EU is also lacking. The European Parliament is certainly junior to the Commission. The European Parliament elections do not produce a government, so the Parliament has no power or authority to execute a mandate. It cannot, for instance, decide to repeal any EU laws – it cannot even directly initiate any laws. No matter what the European Parliament thinks about an existing piece of EU law it cannot force a change. The unelected Commission can completely ignore the European Parliament.

The fact that the EU institutions make decisions behind closed doors which override national democracy often made at the behest of one particular lobby is nothing less than a scandal.

The European Commission is not the only EU institution that is adding to the legislative morass. A member of the Commission Legal Service blames another branch of the EU, the European Parliament. ‘The European Parliament, under the co-decision [ordinary] procedure, is allowed to propose uniformed, irrational, impractical amendments, safe in the knowledge that they have no responsibility for implementation 9.’ Other EU institutions are also part of the problem as any ambiguity is clarified by the European Court of Justice who inevitability add evermore complexity to EU law; which once in place is extremely difficult to repeal. EU rules resemble the complicated financial devices bankers use like their debt swaps and derivatives. Few in the banking sector understood how they operated in practice let alone the risks involved. Complex EU law is equally economically damaging.

Roman Herzog, the former President of the Federal Republic of Germany and the German Constitutional Court, wrote that the,

‘ECJ deliberately and systematically ignores fundamental principles of the Western interpretation of law… and invents legal principles serving as grounds for later judgements. They show that the ECJ undermines the competences of the Member States even in the core fields of national powers 10.’

The process of law making in the EU is fundamentally anti-democratic. The rules of the European Union codified in the EU treaties prevent national democratic procedures, whether by votes in Parliament or referenda, from amending let alone abolishing a single one of these legal measures.

This legislative burden in itself is seen as a cost too far. What is more, it creates a number of serious implications for any nation-state that claims to be a self-governing democracy.

Yet there is a more compelling reason, and one which turns the pro-EU arguments for staying in the EU on its head.

This is the question of influence. It is claimed that Britain has more of a say in international affairs as a member of the EU. This assertion, however, is false. The voting in the Council of Ministers proves this.

From July 2009 to June 2012 Britain voted against the majority more often than any other state. The UK finds itself in a minority in nearly 10% of votes. What is more, Britain’s position has been in the majority on the fewest occasions. This shows where influence truly lies. And it signals that the UK is often without real influence in the EU’s Council of Ministers. In the votes that were not unanimous Britain was in the minority on nearly 30% of the votes. Of the votes where reservations were recorded 10% came from the UK. And when formal statements of concern were issued, again the highest amount came from the UK 11.

It is clear therefore that the battle over influence has been lost before the vote actually takes place. Therefore it appears that the UK actually has little influence and only a limited amount of authority in the EU. It is not a system that is working in the British national interest.

There is also an international dimension at work and remains behind the initiation of many EU rules. There is a plethora of UN sponsored standard setting agencies which produce proposals for legislative standardisation across continents and beyond. An increasing amount of what we know as EU legislation is actually originating above the EU 12. The EU recognises as part of the case law underpinning the workings of the European Union that international law is to be incorporated into EU law which therefore, via Brussels, becomes the law of each and every member state. The legal decisions of the European Court of Justice which confiorm this are: Case 104/81, Kupferberg, Case C-192/89 Sevince and Case C-277/94 Taflan-Met.

Regulation ranging from agricultural produce to increasingly some areas of building control is increasingly decided by UN Standard setting bodies that sit above the EU. One of their main aims is to eliminate technical non-barriers to trade. This is where much of the legislation that is important to the facilitation of trade is actually decided. In this major area the EU has become almost redundant with much now originating from the United Nations Economic Commission for Europe.

The process of international law making for European Union members has become one where a common EU position is derived at. This limits the UK’s ability to present its own viewpoint. Without this a nation cannot have any real influence. EU member states then conform to that position when negotiating international standards in the numerous transnational organisations. Once these bodies propose the rules the EU then adopts these regulations and imposes them on the member-states. Through this system Britain is hit by a double-whammy of influence impediments and loses out twice. Firstly in discussions with member states where the British point of view may not necessarily prevail and the agreed common EU negotiating position may not represent the UK’s national interest. Then secondly the new international standards are adopted by the EU and proposed as an EU regulation which then becomes law. And regardless of whether or not these rules suit the UK as the new standards are now European Union regulations they have to be obeyed and will be enforced by the courts. What is more, they cannot be undone by the UK’s democratic process.

In some instances the UK does not even have a seat at the table where international matters are decided. Often the debate surrounding the European Union centres on the issue of trade. However, as a member of the European Union the UK is not even part of the discussions on matters surrounding the exporting and importing of goods and services. In world trade talks Britain, along with other EU states, is represented at the World Trade Organisation (WTO) by a member of the European Commission; not by a representative of the UK nor of any other individual EU member-state.

Contrast this with Norway’s and Switzerland’s position. They have 100% of their own vote on global bodies passing global trade rules. Within the EU the UK has just around 12% say in the formulation of the European Union’s position. Interestingly both the WTO and the Advisory Centre on WTO Law are also based in Geneva, outside of the European Union.

Having the EU speak for the UK is only effectual if Britain’s interests align with those of the other EU members. Although the UK and nations on the continent are geographically close many European states have differing needs and a different world outlook.

There are alternatives to EU membership that are available to the UK that will allow the UK to have full access to the EU’s internal market but also have more influence over the setting of global and EU regulation.

Norway has more influence in world affairs as an independent state than the, subsumed within the EU, UK. Norway an EFTA/EEA member has actually been described as a ‘leader’ in EU rule making. According to the Paris based Organisation for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD) Norway has lead the EU in the formulation of environmental legislation 13. The voting patterns in the Council of Ministers show that Britain is often the most isolated state inside the EU.

Britain will be better off re-joining the European Free Trade Association. EFTA managed to conclude such an arrangement with South Korea long before the EU. EFTA’s trade deal came into force on 1st September 2006 whilst the EU’s accord with the democratic part of Korea finally entered into force nearly 5 years behind the one which Iceland, Liechtenstein, Norway and Switzerland were already benefitting from. Iceland, a non-EU state, was the first country in Europe to agree a free trade deal with China, Switzerland second. EFTA also reaches free trade agreements with other states. Yet, the EU denies the UK the right to establish its own trade and investment treaties with emerging economies around the world.

The UK’s should have an active and independent role in the UN Sponsored standard setting agencies and not be hemmed into little declining Europe. It is time to leave, it is time for Britain to think global.

- http://ec.europa.eu/research/social-sciences/pdf/global-europe-2050-summary-report_en.pdf

- Office of National Statistics Pink Book 2012 Chapter 9, Table 9.2 Current Account Credits

- http://unctadstat.unctad.org/UnctadStatMetadata/Classifications/Tables&Indicators.html ; OECDstat Dataset: Foreign direct investment: positions by industry, Reporting country Norway; WTO, Trade Policy Review: Switzerland and Liechtenstein, Table 1.4 Foreign direct investment, 2008-11, 23 April 2013 : http://www.wto.org/english/thewto_e/countries_e/switzerland_e.htm

website: http://statistics.cb.is/en/data/set/

- https://www.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/221513/eu_finances_2012.pdf pages 14-17

- http://www.publications.parliament.uk/pa/cm201012/cmselect/cmenvaud/879/879vw27.htm

- http://www.oecd.org/general/thedohadevelopmentroundoftradenegotiationsunderstandingtheissues.htm

- http://www.worldcommercereview.com/publications/article_pdf/66

- http://euobserver.com/economic/22610

- Bellis, Robin, “Implementation of EU legislation. An independent study for the Foreign & Commonwealth Office, 2003,

- http://www.cep.eu/fileadmin/user_upload/Pressemappe/CEP_in_den_Medien/Herzog-EuGH-Webseite_eng.pdf

- Agreeing to Disagree: The voting records of EU Member States in the Council since 2009, VoteWatch Europe Annual Report, 2012

- North, Dr Richard, The Norway Option: Re-joining the EEA as an alternative to membership of the European Union, the Bruges Group, 2013, pages 10 - 28

- OECD, Environmental Performance Reviews, Norway 2011

http://www.constructif.fr/bibliotheque/2015-3/le-royaume-uni-doit-quitter-l-ue.html?item_id=3456&vo=1

© Constructif

Imprimer

Envoyer par mail

Réagir à l'article